Accused Can Reconsult Counsel Before Police Questioning if Police Conduct Undercuts Initial Advice: SCC

Cristin Schmitz

Originally published in Law360™ Canada, © LexisNexis Canada Inc.

In a judgment that sheds new light on the “implementational duty” of police to provide a detainee with a reasonable opportunity to consult counsel, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled 9-0 that a detainee must be given the opportunity to reconsult with a lawyer before being questioned by police in circumstances where it is objectively observable that police conduct has caused “the detainee to doubt the legal correctness of the advice they have received or the trustworthiness of the lawyer who provided it.”

R. v. Dussault , written by Justice Michael Moldaver on behalf of the top court, provides guidance on whether and when police are required to go beyond providing a detainee/accused with an initial opportunity to consult counsel before police begin their interrogation: R. v. Dussault, 2022 SCC 16.

The general rule set in the leading case of R. v. Sinclair, 2010 SCC 35, stipulates that in normal circumstances, once a detainee has consulted once with counsel, the police are entitled to begin eliciting evidence from the detainee.

However, Sinclair recognized three categories of “changed circumstances” after the initial consultation with counsel that can renew a detainee’s right to exercise the s. 10(b) Charter right to consult counsel: (1) new procedures involving the detainee; (2) a change in the jeopardy facing the detainee; or (3) reason to believe that the first information provided was deficient.

Justice Moldaver’s judgment elaborates on the third category of exception to the general rule.

In particular, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that

[...] the right to counsel may be renewed if police “undermine” the legal advice that the detainee has received — which can occur, for example, when police undermine confidence in the lawyer who provided that initial advice.

“A detainee’s confidence in counsel anchors the solicitor‑client relationship and allows for the effective provision of legal advice,” explained Justice Moldaver, who was himself a prominent Toronto defence counsel before he joined the bench.

“When the police undermine a detainee’s confidence in counsel, the legal advice that counsel has already provided may become distorted or nullified,” Justice Moldaver said. “Police are required to provide a new opportunity to consult with counsel in order to counteract these effects.”

Justice Moldaver elaborated that such “undermining” is not limited to police intentionally belittling defence counsel or intentionally undercutting the legal advice first received.

“Police conduct can unintentionally undermine the legal advice provided to a detainee,” Justice Moldaver observed. “The focus should remain on the objectively observable effects of the police conduct, rather than on the conduct itself.

“Where the police conduct has the effect of undermining the legal advice given to a detainee, and where it is objectively observable that this has occurred, the right to a second consultation arises,” he held. “The purpose of s.10(b) will be frustrated by police conduct that causes the detainee to doubt the legal correctness of the advice they have received or the trustworthiness of the lawyer who provided it.”

University of Calgary law professor Lisa Silver told Law360™ Canada “Justice Moldaver does a nice job in the decision of reminding us of the importance of the solicitor-client relationship.”

She highlighted Justice Moldaver’s endorsement of Ontario Court of Appeal Justice David Doherty’s observation in R. v. Rover, 2018 ONCA 745, that the right to counsel is a “lifeline” through which detained persons obtain legal advice and “the sense that they are not entirely at the mercy of the police while detained,” calling it “a stark reminder of counsel’s role in the justice system” and in animating a client’s Charter rights.

A key takeaway of Dussault is that police “should be very careful when speaking of counsel, and vigilant in listening to the detainee,” Silver advised. “Also, the Crown should be careful in giving advice to the police based on case law,” Silver said. “In this case, the Sinclair decision was not a full answer to the situation because it was still open to interpretation. That interpretation can change based on the context. Defence need to be vigilant in their interactions with their client and the police when a client is detained and need to ensure that their client’s needs and instructions are known to police and recorded by counsel.”

Silver said one difficulty she has with the Supreme Court’s latest decision on s. 10(b) is that whether counsel’s advice has been undermined will only be determined after-the-fact, in court.

“I am not convinced that police will be in a position to know or realize that their conduct is in effect undermining confidence in counsel,” she explained. “Therefore, they will not be able to operationalize the right to reconsult.”

She cautioned that police should refrain from commenting on counsel at all “or face difficulties in determining whether they have triggered the right to reconsult. For instance, one of the ways a right to reconsult arises is when the detainee’s jeopardy changes. This would be readily observable by the police. But knowing when there is an undermining of advice, unless intentional, will be difficult.”

Anil Kapoor of Toronto’s Kapoor Barristers, who with Victoria Cichalewska represented the intervener Criminal Lawyers’ Association, said he sees the main takeaway from the decision as “the police should avoid using the tactic of denigrating counsel’s advice or role to persuade people to abandon their right to silence. That is impermissible.”

The Supreme Court dismissed the Quebec Crown’s appeal from a Quebec Court of Appeal judgment ordering a new trial for Patrick Dussault, who was convicted of second degree murder by a jury in 2016: Dussault c. R ., 2020 QCCA 746.

The Court of Appeal concluded that police violated Dussault’s right to counsel and, pursuant to Charter s. 24(2), excluded an incriminating statement Dussault made to police when they interrogated him without fulfilling their duty to provide him with a reasonable opportunity to consult counsel.

Justice Moldaver said that the appellant Crown properly conceded at the Supreme Court that if the accused’s Charter right to counsel was breached by police, his statement should be excluded under s. 24(2).

Justice Moldaver concluded that “in this case, the conduct of the police had the effect of undermining and distorting the advice that Mr. Dussault had received. The police ought to have offered him a second opportunity to re-establish his ‘lifeline’, but they did not. In failing to do so, they breached his s.10(b) rights.”

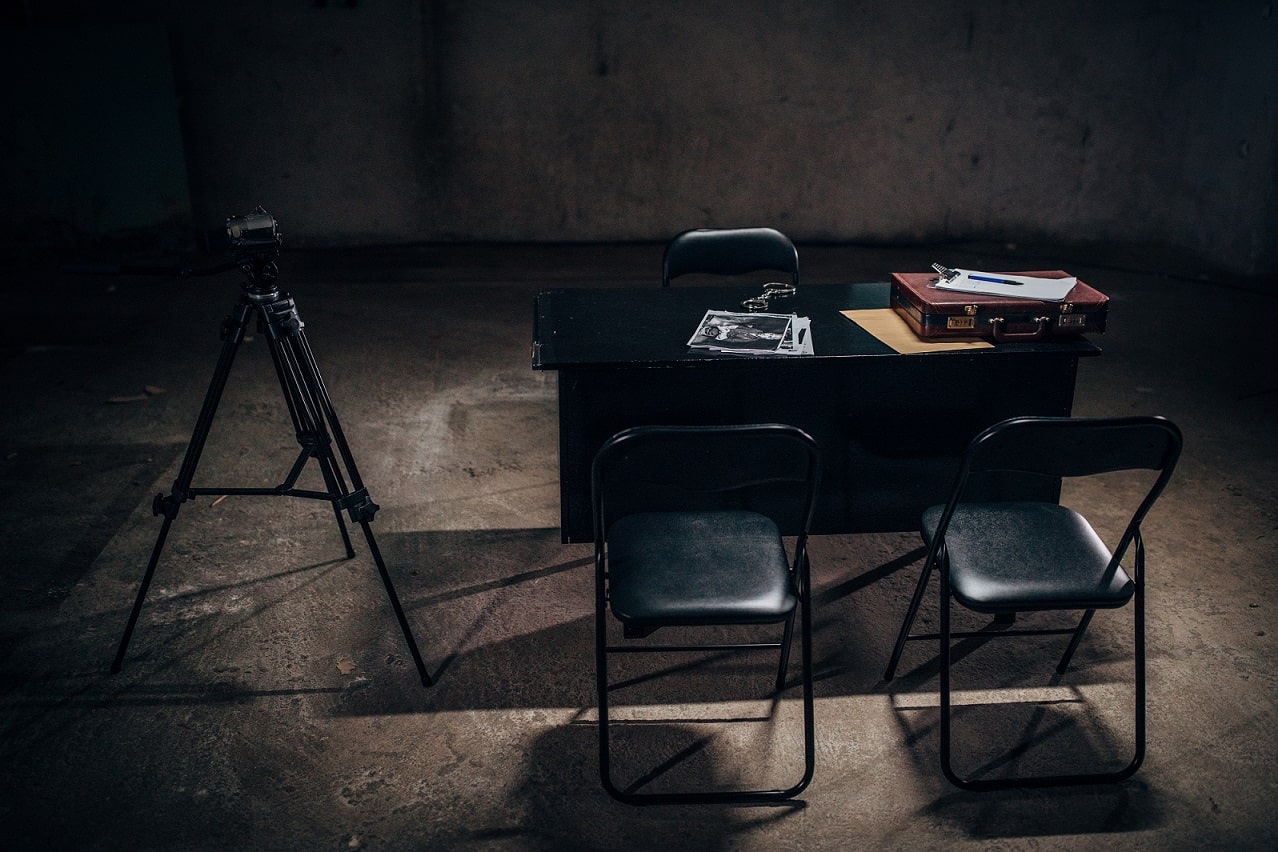

Dussault was arrested in August 2013 on charges of murder and arson. The police informed him of his rights, including his right to counsel under the Charter. At the police station, the accused spoke to a lawyer by phone who explained the charges against him and his right to remain silent. The lawyer got the impression that the accused was not processing or understanding his advice. When the lawyer offered to come to the station to meet Dussault in person, the accused accepted. The lawyer then spoke with a police officer, told him he was coming to the police station, and asked that the investigation be suspended in the meantime. The police officer responded that this would be no problem or no trouble. The lawyer then spoke again with the accused. He told him he was coming to meet with him in person and explained that Dussault would be put in a cell in the interim.

Counsel advised Dussault not to speak to anyone.

But after a conversation between the police officer and the lead investigators on the case, police decided counsel would not be permitted to meet with the accused. The police officer informed the lawyer of this by phone. Counsel nevertheless came to the police station, but was not allowed to speak with the accused.

The police officer later went to Dussault’s cell and told him that another officer was ready to meet with him. Dussault then asked whether his lawyer had arrived, to which the police officer responded that the lawyer was not at the police station.

Police then interrogated Dussault, who made an incriminating statement to them. The trial judge found that the accused had exercised his s. 10(b) right to counsel and that police could reasonably assume that he had done so in a satisfactory manner. Accordingly, she rejected Dussault’s request to exclude his incriminatory statement.

In finding a s. 10(b) violation, Justice Moldaver reasoned that two separate acts of the police officer combined to have the effect of undermining the legal advice provided to the accused.

“In refusing to permit the lawyer to meet with the accused, the police effectively falsified an important premise of the lawyer’s advice — i.e., that the accused would be placed in a cell until the lawyer arrived,” he said. “Second, the police officer misled the accused into believing that his lawyer had failed to come to the station for their in‑person consultation. During the interrogation, the accused repeatedly expressed that his lawyer had told him he would be there; he stated his belief that his lawyer had never actually arrived; he openly questioned why his lawyer had given him the advice that he had given; and he implied that his lawyer’s failure to show up had left him feeling alone.”

“When these statements are taken in their totality and in light of all the relevant circumstances, it is clear that there were objectively observable indicators that the legal advice given to the accused had been undermined,” Justice Moldaver held.